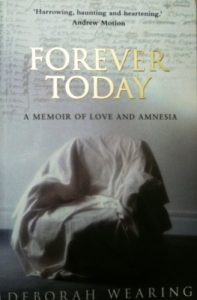

How far can you have a personality without memory of your own story? Today, as our society includes ever increasing numbers of people with dementia, that question is asked more and more often. Clive Wearing is at the extreme end of those with no memory, although in his case the loss of memory followed an encephalitis. In Forever Today, his wife Deborah describes Clive and his daily struggles with encountering the world and himself in it. It is poignant, upsetting, at times comedic, and profoundly thought-provoking about what things come together to make us human. Various clips and documentaries are also available on the web.

How far can you have a personality without memory of your own story? Today, as our society includes ever increasing numbers of people with dementia, that question is asked more and more often. Clive Wearing is at the extreme end of those with no memory, although in his case the loss of memory followed an encephalitis. In Forever Today, his wife Deborah describes Clive and his daily struggles with encountering the world and himself in it. It is poignant, upsetting, at times comedic, and profoundly thought-provoking about what things come together to make us human. Various clips and documentaries are also available on the web.

Clive Wearing’s episodic memory loss is so severe that he cannot remember the sensations of his own body from a few moments before the present, and so he always feels as though he has just woken up from a coma, that he is seeing the room he is in for the first time, and is aware of the person he is with for the first time – “I am seeing everything properly now!!!” There is such a profound emptiness for the time before the present that Clive repeatedly thinks he must have been dead. This is poignantly clear from pages of his diary with a long succession of entries recording the time of writing and his statement that he has woken up, many entries only 2 or 3 minutes apart, and many of them deleted. What he says chimes with neuro scientific theory that subconsciously we need to have regular sensory updates about our body and our surroundings in order to maintain a body image and sense of the world.? (See for example Groh 2014)

Wearing was a professional musician before his accident, running a choir, and heading up classical music programming at what is now BBC Radio 3. Even after he lost all memory for events he retained the skills for conducting a choir or playing the piano – so when he was on one occasion led to a podium with his choir waiting for him, he was still able to conduct them in a known piece of music, even though he did not know he had done it moments after the singing stopped and wondered why all the people were there. There are video clips of him playing the piano, prompted to play by the notes on the page, although unable to remember what had happened moments before. He is able to play patience with playing cards, but is forever puzzled by how the cards came to be laid out in front of him after he looks away or is distracted, even devising a musical notation code to quickly jot down the layout, but noting in his diary that “cards NOT laid out by me”.

He still retained some memory for faces, and the names associated with them, although there were some gaps for the years immediately prior to his illness (retrograde amnesia), resulting in an expectation that his children should be younger than they were. He is touchingly ecstatic when his wife Deborah returns to his room. Even if she has only gone out for 2 minutes he greets her as though she has been away for weeks, and asks where she has been. Initially his vocabulary was also diminished but this steadily returned, enabling him to repeat the same puns over and over again, not realising that his hearers had already heard them from him two minutes earlier. The description of the features of Clive’s memory loss are described in Chapter 6, ‘Life with No Memory’.

One of the fascinating aspects of this book is the way in which some aspects of Clive’s memory improves. Although his diaries are still full of the statements that he has just woken up, he becomes familiar with the new coinage post-decimalisation, he appreciates that the Millennium is happening, he can remember in which cupboard cups and coffee are kept. The improvements are small, but reminiscent of those seen in the other man famous for his amnesia, Herbert Molaison. (Just as Clive Wearing was CW in the scientific literature, so Herbert Molaison was HM.) Suzanne Corkin tells of how Molaison was able to draw a rough plan of his new home, after several months of walking around it (Corkin 2013).

The emotional heart of this book is the relationship between Clive and Deborah, whose life is traumatically disrupted by her husband’s encephalitis. The distress of losing – but still having to look after – someone like Clive is powerfully described, and eventually she runs away to get a job in America. It would be hard to blame her, but she still feels tremendously guilty. She returns, but the dislocation caused by Clive’s loss is profound, and every part of her life seems to be on hold. Eventually she turns to the consolation of religion, without which, it seems, she might have had a complete breakdown. Strengthened in the knowledge that Clive is improving in a residential home with a good key-worker who can play piano duets with him, Deborah is eventually able to make a new life in Bath. But her apart-together life with Clive continues, as she continues to visit him, and they even renew their marriage vows. It is a sad and moving story in which a loving relationship is distorted forever by the loss of memory, to the extent that a normal conversation is almost impossible. But as for personality? Clive has it in spades!

The two documentaries about Clive, the first made in 1986, which shows his intense anguish and distress at his situation, with consequent irritability, and the second made twenty years later, allow us to see him playing the piano, writing in his diary, and welcoming people who had returned to his room after a few minutes away as though they were long-lost friends. The Man with the Seven Second Memory is particularly good in showing how Clive’s relatives, his wife, his sons and daughter, and his sister are so distressed by his predicament, and serve as excellent parallel sources to Deborah’s memoir.

References:

Suzanne Corkin (2013) Permanent Present Tense, London, Allen Lane

Jennifer Groh (2014) Making Space: How the Brain Knows Where Things Are, Harvard, HUP

Deborah Wearing (2005) Forever Today, London, Doubleday

Prisoner of Consciousness (1986) Channel 4 The Mind documentary, dir. John Dollar, pres. Jonathan Miller (47 min.)

The Man With The Seven Second Memory (2005) ITV Real Stories Medical documentary (48 min.)