Black Lives Matter. And consequently, the discussions about ‘decolonising the curriculum’. Unfortunately the discussions have so far often centred on the difficulties of defining ‘BAME’, ‘decolonisation’ etc., which could be an excuse for inaction.

So what does ‘decolonisation’ mean in Physiotherapy? How do you ‘decolonise’ a profession that developed in the modern west, and at times, to be honest, as an occupation for middle-class girls?! ‘Decolonisation’ is hard to define, and certainly is not limited to issues of language. But in general, the physiotherapy textbooks in English are predominantly American, British or Australian. What’s more, we English-speakers in Coventry rarely bother to consult sources in exotic languages like French or German, let alone anything featuring non-Roman lettering. Thank heavens in neuro rehab for the Spinal Cord Injury website (https://elearnsci.org ) with contributions and case-studies from all around the world.

What of published illness narratives, my own specialist area? I comb through my bookshelf and my reading list of over 300 titles, and I try to spot any voices from a BAME background. Most of the personal illness stories that were originally written in a non-English language are by European authors: Jean-Dominique Dauby, Antoine Leiris, Bruno de Stabenrath, Marieke Vervoort, etc. What else can I find? There are several contributions by doctors whose forebears recently lived on the Indian sub-continent or Africa: Atul Gawande, Paul Kalanithi, Abraham Verghese. But these are also people who are part of the dominant Western culture with an excellent knowledge of English literature as well as of Western medicine. Significantly, Ved Mehta’s accounts of blindness (1958, 1982) could also be seen as the journey of an Indian from a Bombay orphanage through Oxford University and Harvard to become an established writer on the New Yorker, in other words of joining the white social elite.

There are a few narratives by BAME personalities whose personal disasters have made them even better known: Michael Watson (2004), Malala Yousafzai (2013). Very rarely there are classics in other languages from completely different cultures that are translated into English – like the accounts of autism by Naoki Higashida (2013). (Even then, would The Reason I Jump have been published in English if an established English novelist had not married a Japanese woman, and if they had not parented an autistic son?)

But there are very few BAME accounts of chronic illness in my lists and shelves. Are they around but I just do not know about them? Or is there a publication bias – they are written but rejected by publishers? Or is illness writing not part of some cultures – health is so important that ill-health is something to be ashamed of? Is it only the wealthy and highly educated that have the impulse, confidence and resources that might drive them to write about their misfortunes, and get those writings published? In other words, are we talking about the same recurring differences in wealth and class that inhibit BAME achievement in other fields?

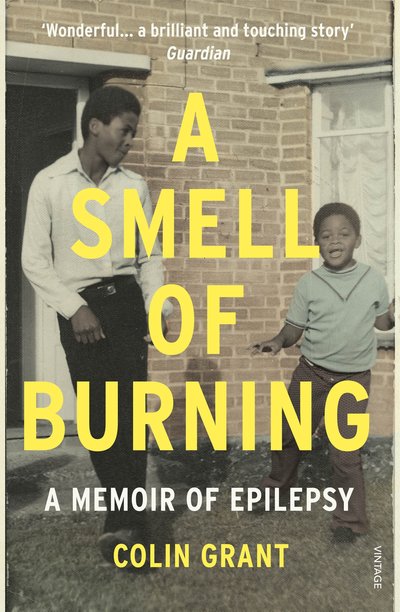

Here is an instructive example: two accounts by young men whose brothers had epilepsy about epilepsy’s effects on the wider family. One is by an English aristocrat, whose brother could, and did, play seigneur at the annual fete in the family castle’s gardens (Fiennes 2009), and the other is by a son of the Windrush generation (Grant 2016). Powerlessness is a recurring theme in Colin Grant’s account of epilepsy within a North London Jamaican immigrant household. Colin himself becomes a medical student, and thus joins the Western educated club – but still cannot help his brother Christopher or discuss epilepsy easily with the rest of the family. (Epilepsy is in Jamaican culture a subject of mystery, magic and shame.) In some ways the two accounts run in parallel, for both epileptic brothers will eventually die in status epilepticus. And the narrating brothers both struggle with their feelings of impotence and loss. The account by William Fiennes is magical, with an unforgettable evocation of place. Yet, if I had to recommend one narrative for the physiotherapy student to read, I would have to recommend that by Grant, for its relevance to the people our students will meet.

Decolonising the curriculum will take effort. It will involve conscious deconstruction of societal barriers of inertia, and differences in wealth and advantage built over generations. Personally, I will have to search even harder for illness narratives from a BAME background. And I need to prioritise those BAME narratives that I have heard about but never read. So action number one: it’s time to overcome inertia and pre-order Audre Lorde’s Cancer Journals which are due for reissue in November 2020.

References:

Fiennes, William (2009) The Music Room, Picador

Grant, Colin (2016) A Smell of Burning: A Memoir of Epilepsy, Jonathan Cape

Higashida, Naoki (2013) The Reason I Jump, Sceptre

Kalanithi, Paul (2016) When Breath Becomes Air, Bodley Head

Lorde, Audre (1980, new edition Nov 2020) The Cancer Journals, Penguin

Mehta, Ved (1958) Face to Face, Collins

Mehta, Ved (1982) Vedi, Oxford University Press

Watson, Michael with Steve Bunce (2004) The Biggest Fight: Michael Watson’s Story, Time Warner Books

Yousafzai, Malala with Christina Lamb (2013) I am Malala, Weidenfeld