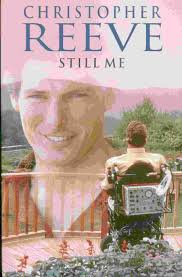

Christopher Reeve was Superman on the big screen. Which is what made his catastrophic high cervical spinal cord injury in 1995 all the more poignant. Still Me is his story.

Christopher Reeve was Superman on the big screen. Which is what made his catastrophic high cervical spinal cord injury in 1995 all the more poignant. Still Me is his story.

This is another Hollywood autobiography that some of my international Masters students have found difficult, possibly because in chapter 1 Reeve portrays himself as having the best of everything, the best riding lessons, the best tutors, the summer residence in Vermont etc. Later, even his neurosurgeon has to be one of the best, with a CV ‘roughly the size of a county telephone directory’. (Perhaps there is a sense that the losses are all the more tragic when you have everything?) The difficulties my students express are a pity, because Reeve’s heart-felt message is that the pre-accident person – with his feelings, ambitions, experiences and history – is the same post-accident person, whatever has happened and however curtailed his new life. And that must be true of many people who experience crisis, even those that emerge from trauma with a new outlook on things.

The message (‘Still Me’) emerges through the structure of the book, in which each chapter about Reeve’s accident and rehab alternates with a chapter about his pre-accident life, his childhood, his early years in acting, and his life as the actor who was Superman. In other words, the Christopher Reeve pre-accident is still there in the wheelchair bound person relying on ventilator support. He is the thread that is common to the pre- and post-accident story. Which begs the question, how far are we the same person as we were 20 years ago, even though we share the same experience of before that time? Each of our cells has regenerated its many chemical components, just as no cathedral retains any of its facing stones from when it was first built. So what makes me ‘Me’, and how far are is this me continuous with the ‘Me’ of 20 years ago? Perhaps it is just our story that links those characters, and how our nearest and dearest think of us.

Chapter 2 is about the immediate treatment of Reeve’s SCI, including surgery and being nursed, his period of denial and embarrassment, the fearful nights, and the dreams of moving and being intact. Reeve tells honestly how in that crisis period his whole outlook was selfish and self-centred, just to be able to survive. And how he appreciated the letters of encouragement, from friends and strangers. Most movingly, he tells how his wife Dana makes a commitment to support him.

For a physiotherapist Chapter 4 is a fascinating insight into how the person in rehabilitation sees it from their point of view. Reeve’s panicked feeling of being a fish flopping about in a boat, when his breathing tube pops off, is completely convincing. The terror of undergoing new activities, like having a shower, during which he was totally dependent on the carers getting things right is beautifully described and rings very true. Even sitting upright in a wheelchair is enough to bring on an anxiety attack when you are not used to being vertical and you have a long thorax over which you have no control. ‘Compassion and generosity’ in the clinicians that helped him in his rehabilitation was obviously vital. And the rehab assistants who interacted the most with him, but were paid the least, were the most important for his recovery. Exercise regimes, catheter blockages, efforts to improve respiratory function, the first engagements with the world outside hospital – all are described from Reeve’s perspective.

Chapter 10 tells the story of how Reeve returns to the film industry to direct a film from his wheelchair, which is an interesting exercise in what is possible if you have the motivation and the financial resources, but less applicable to those who don’t. However, it contributes to the theme of continuity of character, interests and ambitions. And it is important in the theme of not allowing disability to define and limit a person, but for everyone involved to work to overcome barriers. Although Christopher Reeve writes about his adjustment to his SCI, there is also a strong sense that he rebels against it, and that he is not prepared to put up with the restrictions that it seems to demand.

Christopher Reeve (1998) Still Me, London, Century Books