Published illness narratives are often those by public personalities or by established writers who happen to have encountered illness or disaster. However, there is a third class of narratives which do not have the commercial potential attractive to publishers, and which are therefore self-published. Each narrative of this type features the author’s need to have their voice heard.

Published illness narratives are often those by public personalities or by established writers who happen to have encountered illness or disaster. However, there is a third class of narratives which do not have the commercial potential attractive to publishers, and which are therefore self-published. Each narrative of this type features the author’s need to have their voice heard.

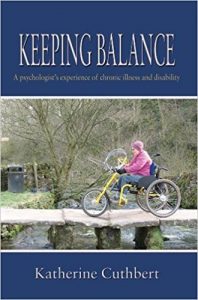

Katherine Cuthbert was a psychology lecturer at Crewe and Alsager College of HE, who has self-published her narrative of her seventeen year experience of Multiple Sclerosis. She is an amateur writer, but her writings provide an authentic and individual account. In particular she portrays very clearly the processes of adjustment required to cope with MS and the increasing restrictions MS imposes. In practical terms for example, Cuthbert experiments with different forms of cycle as her physical abilities decline, starting from a normal pedal bike through sharing a tandem with her husband, to using specialised tricycles and hand-cranked bikes, with plenty of details provided on the best retailers and support structures.

The writer is very up-front about using her knowledge as a psychology lecturer to inform her account. In the chapter ‘MS and my experience of it’ she describes her diagnosis and her initial responses to being off sick, her sensory symptoms, visual difficulties, her worries about her job, and continuing to do some academic and supervisory work from home. Like many people with MS, Cuthbert experienced a remission after her initial diagnosis. The insidious return of symptoms was upsetting, in particular an increased reliance on her stick and frequent falls.

She discusses the uncertainty of chronic disease, and the ambiguous identity issues posed – the individual is at different times ‘ill’, ‘normal but with a chronic disease’, or just ‘normal’ according to the different circumstances. There is a useful explanation of the concepts and techniques such as ‘benefit finding’, emotional resilience, control and ‘self-efficacy’, although in the moments that Cuthbert becomes the psychology lecturer the personal impact of her memoir lessens. In her own situation she tries to use positive psychology, despite the emotional let-downs when temporary symptomatic improvements are not maintained. Cuthbert’s explanation of distinguishing between what can and cannot be controlled in the context of her own choices and her struggles to make those distinctions, would be useful for anyone with a chronic disease.

This is, overall, a very positive personal account of a life with MS, and there is much to recommend it for people who have been newly diagnosed. The final chapter’s title, ‘Disabled body but positive self?’ is a summary of the whole book. Or perhaps a better image would be Katherine and her husband Pete’s self-build project, a house-building enterprise which took several years, but took into account the possible decline in the author’s physical abilities, thus enabling them to live as they wanted within the constraints set by MS – a positive image of self-efficacy at work.

Cuthbert, K (2010) Keeping Balance: a psychologist’s experience of chronic illness and disability, Kibworth Beauchamp Leics, Matador