Tim Rushby-Smith is not afraid to be honest, whether it is about bowel accidents, or about other people’s attitudes to his spinal-cord injury, or the apparently idiosyncratic fluctuations of his own emotions. But at the same time as sparing no one, including the surgeons and physiotherapists, he manages to inject a humorous tone that makes his memoir both informing and fun.

Tim Rushby-Smith is not afraid to be honest, whether it is about bowel accidents, or about other people’s attitudes to his spinal-cord injury, or the apparently idiosyncratic fluctuations of his own emotions. But at the same time as sparing no one, including the surgeons and physiotherapists, he manages to inject a humorous tone that makes his memoir both informing and fun.

Tim’s injury was at the bottom of his thoracic spine, giving him full use of his upper limbs and, with practice good trunk control. He even starts the ambitious (and precarious) process of learning to walk with calipers and crutches. His rehabilitation experience and life after injury is, in this sense, different from those of Henry Fraser (cervical level) and Claire Lomas (thoracic).

There are also differences in tone. Whereas Henry Fraser, with a cervical injury, decides very early that he needs to accept his disability, and to work from where he is, TRS struggles throughout the year described here with a tussle between acceptance and struggle: how far he has to come to terms with his injury if he is not to be consumed by negative emotion, and how far to struggle to push the boundaries of his abilities as they have been redefined by that injury. He points out several times that it is only by being bloody minded that he has been as successful as he is in rehab, but that partly comes from a desperate desire to be as free as he used to be. For example, he works fiendishly hard in rehab under impetus of the imminent arrival of his baby daughter, but he reacts with an anguished sense of loss at the sight of a father rescuing a crying toddler from the top of a climbing frame. The balance between these priorities is always changing, and this book is a fascinating insight into this process of adjustment, a process which we realise may never reach a stable equilibrium. Towards the end of the book TRS tells of the family’s trip to Australia, a mark of Tim’s rehab achievements, but a trip that brings new encounters with aircraft loos, and Australian sand.

TRS makes some interesting comments about rehabilitation, and how clinicians can deliver varying advice on things like pain medication or wheelchairs. Often it is the advice of people further on in their recovery, whether in person or via an on-line discussion forum, that deliver the most useful advice. Only when he challenges a physio to try out the technique for bum-shuffling up the stairs does she realise how scary it is.

For the person with spinal injury, or their partners and carers, this book contains gems that rarely reach the published memoirs. Detailed accounts of mishaps with catheters and catheter bags, with bowel control, and experiments with sex, are entertaining as well as useful. Advice on all these topics is available on the web, but TRS gives us the benefit of his experience with a humour and honesty that is truly engaging.

The relationship of Tim with his pregnant partner Penny is an important component in his recovery. Tim reflects at different stages on how the encouragement of Penny and other family and friends is vital to rehab efforts and adjustment. He wonders what it would be like to try to bounce back without that support. And those family and friends have to cope with the reduced pace of things as he insists on doing things independently – the only way to improve. So Tim periodically reflects on the adjustment process that Penny, as a partner whose life expectations have changed abruptly, also has to travel.

Tim uses the useful concept of narrowed zones of comfort. For example, He is proficient at propelling a wheelchair, but the increased height of kerbs in Sydney suddenly reduces his options. Or when he spontaneously decides to buy ice-creams for Penny and himself, he suddenly discovers the impossibility of pushing up a slope and keeping the ice-creams intact. Narrowed zones of comfort also apply to his tolerance of other people’s attitudes to his injury – if they are too pessimistic he is irritated, but if they are too optimistic his response is a cynical ‘what do you know about it?’. It rings very true.

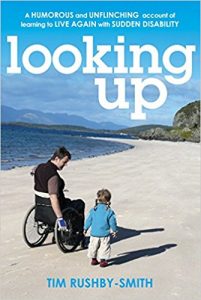

Rushby-Smith, T (2008) Looking Up, London, Virgin Books