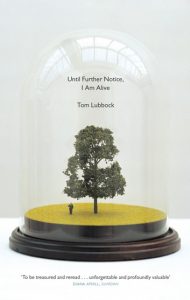

Tom Lubbock’s words live on, even after his death in 2011 from a brain tumour. Some of his art criticism was published as Great Works: 50 Paintings Explored (2011) and English Graphic (2012). His journal of the time from his first epileptic fit in 2008, through his two brain operations, radiotherapy and chemotherapy, chronicles his remaining time with his wife Marion and son Eugene, despite a progressive loss of language, and has been published posthumously as Until Further Notice, I Am Alive (2012).

Tom Lubbock’s words live on, even after his death in 2011 from a brain tumour. Some of his art criticism was published as Great Works: 50 Paintings Explored (2011) and English Graphic (2012). His journal of the time from his first epileptic fit in 2008, through his two brain operations, radiotherapy and chemotherapy, chronicles his remaining time with his wife Marion and son Eugene, despite a progressive loss of language, and has been published posthumously as Until Further Notice, I Am Alive (2012).

This is all very ironic, since words were disappearing for him, for the tumour in his left temporal lobe sabotaged the circuits integral to language. Lubbock’s intelligent and painstaking analysis of his linguistic symptoms and the varying failings in his communication skills, is essential reading for anyone interested in language and in the different forms of aphasia. He was a skilled writer, who enjoyed writing, and who wrote for a living. Long after his first fit, he continued to contribute to the Independent newspaper as its art critic, using dictionaries and other reference works to help him circumvent the growing linguistic difficulties. Luckily for him, and us, his communication abilities seemed to return at night, and although slower, he continued to write, sometimes until four in the morning. The nature of his aphasia varied considerably, and Lubbock noticed and dissected a whole range of functions, from finding words for automatic speech or for deliberate writing, to understanding what he is saying, to hearing other people’s words, spoken or on the radio or TV, to reading a text, aloud or silently, and copying text. Within these functions there are many subfunctions, some of which are normally automatic. Oddly, Lubbock noticed that sometimes communication can continue on an automatic level without him being able to understand consciously what he is saying, or to recall it afterwards, even though he can recognise at yet another level that he is still making sense. He became acutely aware of the interaction of automatic modules that support communication, modules that normally interact without difficulty. At times he made use of these interactions to get around the symptoms, as when he visualises the spelling or first letter of a word that he cannot speak, to facilitate its utterance. (He then points out that aphasia for an illiterate must be different from aphasia for someone who reads and writes.) It is a fascinating exploration of the nature of language, and for that reason alone is highly recommended.

But Until Further Notice is also a poignant and moving account of how a couple and their young son decided how to live the time still available to them, once notice of its imminent end had been delivered. Tom described the three month scans to monitor the tumour, and how the news (good or bad) was given. When his oncologist friend Lucy rang him a day early to deliver good news about one scan, it had ramifications for future scans – the next time he wondered if the absence of an early call was a harbinger of bad news.

For the most part he, Marion and Eugene continue in a normal mode, except when he has to have surgery or has to be admitted to hospital. Lubbock’s tumour is not one to cause pain – the problem is more one of intermittent fits and swelling that interfere with language. So he was able to enjoy a family life until very near his death, watching Eugene develop his own language skills even as his own skills declined. Even reading stories for Eugene becomes difficult and then impossible, and Eugene notices the change.

There is some discussion of how to live in the face of a death sentence – something we all have to do, but ignore at a conscious level since the sentence is so indeterminate. Tom Lubbock runs through the choices: the bucket list option to fill remaining life with pleasure, the desperate and energetic search for all the best actions to prolong life, and his own option, hoping for the best, trusting in local medicine, facing the inevitable when it comes. Indeed, he appears from this memoir to be very little cast down, living in the present normality, enjoying time with Marion and Eugene, perhaps aware that Marion, with thoughts for the future, finds the present more difficult than he. Marion’s own sparkling memoir of this period was published as The Iceberg (2014).

Through all this, one becomes aware of Tom Lubbock’s lively intelligence and humour. Even near the end, when the sentences are shorter and verbs often disappear, Lubbock noted that ‘I find my brain is still busy, moving, thinking…. My experience of the world is not made less by lack of language but is essentially unchanged. This is curious.’ Loss of language is certainly not loss of intelligent interest. Shortly before this he worried about the plot-line of his illness article for the Observer, noting that his current plot was neither the tragic cancer death nor the heroic overcoming, but ‘the shaggy-dog story’ of ‘an ending wanting to be endlessly deferred’.

Brilliant.

Lubbock, Tom (2012) Until Further Notice, I Am Alive, Granta

Lubbock, Tom (2010) ‘Words Fail Me’, Observer article 7 November 2010

Coutts, Marion (2015) The Iceberg: a Memoir, London, Atlantic Books